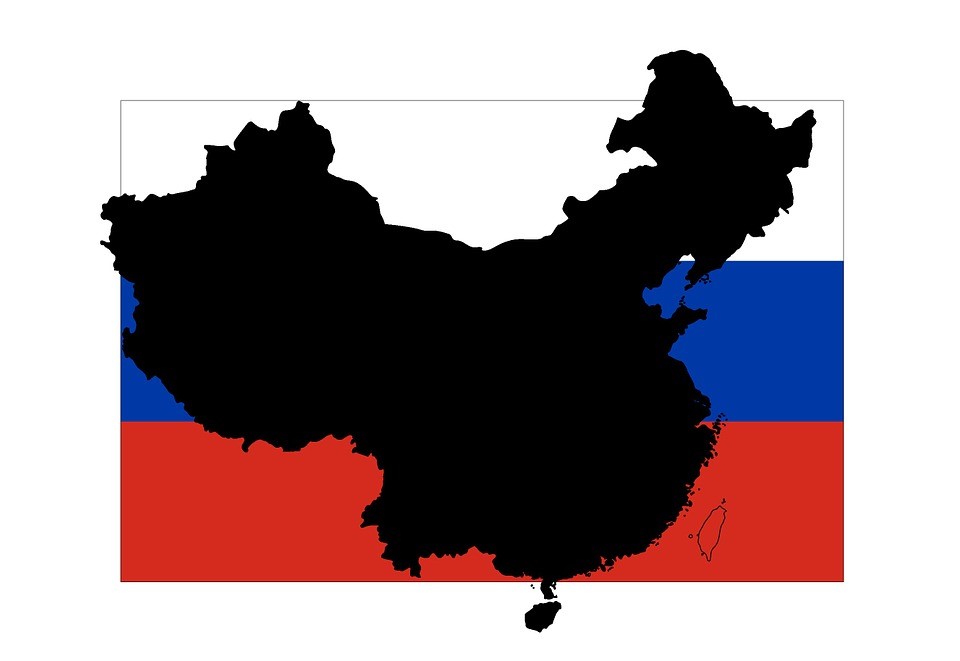

Oh, what troubled webs China and Russia weave….

Last week China abstained from voting to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine in the United Nations. Domestically the CCP is curtailing discussion of the invasion on Chinese social media sites. At the same time this week Beijing pledged $790,000 in aid to Ukraine. It isn’t the only pledge Beijing has made to the country. In December 2013, President Xi Jinping met with former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych in Beijing and signed a promise to defend the independent European country if threatened with a nuclear attack. Although the agreement was not specific in its guarantees, it was typical of Chinese pledges of protection to other non-nuclear states. The reason behind the nine-year-old agreement, only available in Chinese, still baffles nuclear experts. Now that Russia has moved its nuclear forces to a high alert level China faces the potential of responding to Russian aggression toward Ukraine or reneging on its unconditional pledge of support if an invasion of Ukrainian sovereign territory morphs into a nuclear conflict. Putin can’t be happy with China taking a back seat as the world unites against Russia.

A review of Chinese media indicates that Beijing is attempting to back peddle on its commitment to Ukraine by using nuanced language to cloud the issue. Beijing is known for using the connotative meanings of words to interpret documents to China’s advantage. The 2013 agreement with Ukraine is no different. The Chinese government security document uses the word “bao zheng” or “guarantee,” to describe the agreement rather than a more vague term meaning only to “make an assurance.” Today Xi Jinping is moving toward public descriptions more akin to Chinese assurances than an actual guarantee of assistance. While this is of help to Russia, it is not a strong policy of support for Moscow.

Western and Chinese legal agreements differ in many respects. One divisive area typical encountered encompasses the Chinese notion of the “spirit of an agreement.” Intention is a legally binding concept under Chinese law that allows for violations of a written document under certain circumstances. Unlike Western contracts that include extensive Terms and Conditions detailing the possible issues in a dispute, China’s agreements typically are not strictly adhered to by either the government or business community. In China, the “spirit” of an agreement refers to the notion that the parties intend to abide by the agreement unless conditions referred to change from the time of its signing. In China the legal system recognizes changes in environment and, thus, the “spirit of the agreement” to provide flexibility in the terms without Western-style penalties. China is looking to the “spirit” of the agreement with Ukraine as circumstances have changed.

Today Russia maintains a strategic partnership of convenience with China. Nine years ago, Moscow had a similar relationship with Ukraine while China was working to establish its first Belt and Road Initiative in Europe. At the time it appeared China was ready to reap the benefits of aligning with Ukraine. There was no Russo-Ukrainian conflict brewing yet over Crimea to complicate the bilateral relationship. In 2015 China formalized the Kiev agreement when the National People’s Congress rubber-stamped it. However, Ukraine has moved toward improving its relations with NATO and the European Union. China views this as Kiev making changes to the surrounding circumstances while Moscow recognizes it as an increased threat environment impacting Russia’s national security.

The publicity generated from the China-Ukraine agreement recently may be driving a small wedge into the China-Russia relationship. Analysts in the West are not sure. The BBC is reporting that Douyin, China’s version of Tiktok, removed 498 videos and 2,657 conflict comments in the last week. When Chinese media does report on the situation in Russian engagement in Ukraine it does not call it a “war” or an “invasion.”

Disinformation campaigns out of Russia are repeated on Chinese platforms as the truth. Russian state-controlled media is on air in China, where most others are blocked. China Digital Times is reporting that instructions issued to media by the central regulator the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) this month call on “commercial websites, local and self-published media” not to “conduct livestreams or use hashtags” about the Ukraine conflict.

Chinese leaders are not comfortable taking sides this week. Xi Jinping is a strategic thinker who sees that Putin is in trouble and he is distancing China from Russia. He does not want the same negative commentary to befall the leadership in Beijing, especially as it appears Putin is not winning the war as easily as expected. Walking along the top of a fence without falling off on one side or the other is difficult. So far, China has adeptly steered clear of the worst scenarios. Putin may not be so lucky if the world continue to stand strong against the dictator from Moscow.

Daria Novak served in the U.S. State Department