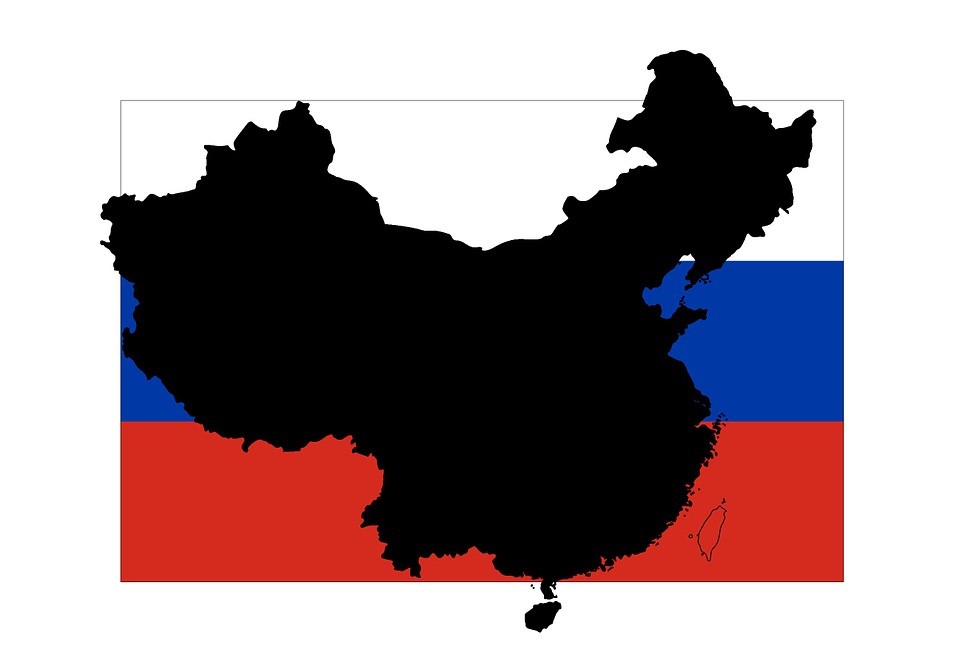

The environment in Moscow is changing – literally. Putin’s growing need to find funds to support his war effort in Ukraine may lead to an ecological crisis for the country and a political challenge for the president himself. He is counting on Chinese firms to develop mines and mineral processing facilities inside the Moscow Oblast. “Putin’s ‘turn to the east’ and his need for Chinese support have pushed Moscow to allow Beijing to develop extractive industries near the Russian capital, making protests against both the Kremlin and China more likely,” according to Paul Goble of the Jamestown Foundation. The spillover of environmental issues into political ones is an unwanted challenge the regime must now address. Local officials in the capital city expect the move will spark protests from the general population living around Moscow and in the Moscow Oblast region adjacent to it.

Previously, the Kremlin sought to avoid controversial infrastructure projects near Moscow that could morph into a political protest movement capable of spreading quickly across the country. Five years ago, the start of a few smaller mining projects on the edge of the capital city initiated protests in a number of smaller areas remote to Moscow, including Shiyes, Siberia, and Bashkortostan. They were easily contained, far from the Kremlin, and did not draw much media attention. It did, however, begin the “not in my backyard” protest movement.

Goble says the transformation of the environmental issue into a politically volatile one is “especially serious when foreigners are involved and [Putin] shows little concern for the ecological worries of the surrounding population.” Putin’s acceptance of the increased risk to his regime and citizenry is an indication of how desperate the government is to fund the war effort. The Kremlin’s need to pay for advanced weapons to combat Ukraine’s arsenal is more acute this year, as the Russian military has been unable to take down the majority of Ukraine’s military drones operating inside Russian territory.

Although the Chinese have a long-standing request with Moscow to develop the mines, Putin held off until recently due to the problematic optics of Chinese involvement, the risk that the exploitation of the mines and related processing industries could spark unrest close to the Kremlin, and environmental concerns over expanding the extractive process itself. Russia has a history of allowing China to mine in other parts of its territory. Although it was never implemented, in 1953 the two countries signed an agreement that allowed China to develop mines and mineral process facilities near Moscow. By early 2023, the Kremlin relented and allowed the Moscow Oblast to sign an agreement with Chinese firms.

Mines were reopened after environmentalists were pushed aside, according to a January report in the Eurasian Daily Monitor. The Chinese firms are involved in oil, coal, phosphorites, and rare earth mining, including titanium and lithium. The Rossiyskaya Gazeta reported on May 19 that the Russian government expects the decision to add 10,000 new jobs this year. According to Goble, “This development will likely stoke problems at home and could ultimately threaten both the Kremlin leader and his alliance with China.” There are strong indications that opening the Moscow Oblast will lead potentially to political protests against Putin for allowing China to take the lead in mining and processing both minerals and chemicals in a region heavily populated by Russians.

Given China’s long history of environmental abuses in the extractive industries, it is highly likely Putin’s opposition will foment unrest in Russia, given the president signed off on the deal. To reduce the regime’s risk, some political analysts in Washington suggest Putin will increase repression of dissent this summer to prevent an upsurge in popular protest. Goble suggests that this approach may be counterproductive as it increases the likelihood of nationalizing the issue and expanding potential protests. It appears Putin is willing to ally himself with China above the Russian people and risk a long-term political and ecological disaster for the nation ton continue his quest to reconstitute the Russian Empire.

Daria Novak served in the U.S. State Dept.