Dictators like to dictate. Chinese President Xi Jinping is no different than other historical figures who used tyranny to control their country’s population. Although some are referred to in books more benevolently than others, a leader who represses the population will likely face a time when the political system he commands waivers in its support of the government’s harsh policies limiting freedom. The “color revolutions,” that once erupted in response to harsh Soviet, Eurasian, and Middle East dictatorships, may soon be making an appearance in China. It seems Xi’s star is beginning to dim after a series of bad economic decisions, loss of public confidence in the government and CCP, and world condemnation over China’s role in the Covid pandemic.

“A storm is brewing,” according to Roger Garside a former British diplomat and author of China Coup: The Great Leap to Freedom.” He predicts that 2023 will be the year that breaks Xi. He argues that if he is correct, “…it will destroy President Xi Jinping, and bring an end to the political system he is determined to defend.” He is not alone in his assessment. Lu Shaye, China’s ambassador to France, concurs that lately the wave of protests in China has “smelled of a color revolution.” When discussing the Chinese protests with journalists he talked about the “blank sheets” of paper held up by protesters. In an acknowledgment that the placards are symbolic of the population’s inability to speak freely, he reminded reporters that “White is a color, too.” It is not, however, the first time the CCP faced challenges from the citizenry or others inside the government.

During the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstration, the head the political section at the Chinese Embassy in Washington was sympathetic to the protesters. His son, by birth part of the political elite, participated in the Tiananmen Square protest. The Chinese government is accused of killing thousands who refused to leave the Square. From behind the white curtains hanging on each side of the front door of the Embassy in Washington, diplomatic hands would appear waiving to the media and American public outside. They were small, but brave, acts of defiance. Thirty-three years ago, China was less connected to the world. The Internet was not widespread inside China and students were restricted in the overseas studies. The global supply chain today has changed as anyone who purchases electronics knows. China is intricately linked to the West. The storm brewing in Beijing today is in part a response to the failed response to the COVID epidemic, an economy that is struggling, and a loss of faith in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Without the “mandate from Heaven,” the CCP is facing a crisis that Garside says marks that beginning of a white revolution. Xi’s recent relaxation and then abandonment of COVID restrictions comes at a very high health and political cost to the regime. Although the strategy has temporarily appeased the public, it revealed a weakness never seen before in the communist regime. The CCP historically is concerned that human rights or other protests could morph into anti-regime sentiment able to threaten the legitimacy of Party rule.

According to Garside, “Never before in the history of the People’s Republic has there been such a manifestation of weakness in the face of public demand.” In response to public demands Xi ordered the lifting of restrictions. He did so, however, without a plan in place to prepare for additional vaccinations, psychological support for the citizenry, or the strengthening of the country’s public health system. Protesters called the regime’s initial restrictions undeserved punishment and suggested that it exposed the inhumanity of the regime.

No freedom of speech is permitted that criticizes the failings of the government, the CCP leadership or the Party. In relaxing health restrictions without adequate planning Xi is walking a narrowing path.

The Party is covering up health data by suppressing the number of cases and COVID deaths. It indicates a grave loss of authority for the communist dictator. As of December, the wait at the crematoria in Beijing is passing five days. By the end of March, some analysts are predicting demand for ICU beds will be ten times the available supply. At the same time as China is experiencing spikes in COVID cases, it also faces mounting economic problems. Domestically the property sector is faltering, local-government-finances are beginning to collapse and there is no abatement in the slow-moving financial crisis. Internationally, trade is weakening with rising unemployment at home. Without a sufficient welfare system in place to support the population through this period, increased unrest could lead to a destabilization of the government and CCP. Xi’s policies are proving counterproductive and alienating the support of those he needs to remain in power. Garside says that “In place of hope, there is disillusion as manifested by a major movement of emigration that is being led, for the first time in history, by rich and power people.” Some young protesters, like Xi’s own daughter, have chosen not to return to China after studying in the United States. It portends an uncertain future for Xi and the CCP. Today, there are a billion mobile phones in China, unlike the 1989 period where the government was able to successfully repress those protesting in Tiananmen Square.

It will be almost impossible for the world not to hear the call for freedom this time. It represents a glimmer of hope for the future and marks a dangerous period in Chinese domestic politics that could lead to new calls by the CCP for repression against those who refuse to accept the legitimacy of the Party.

Daria Novak served in the U.S. State Department, and has lived in China.

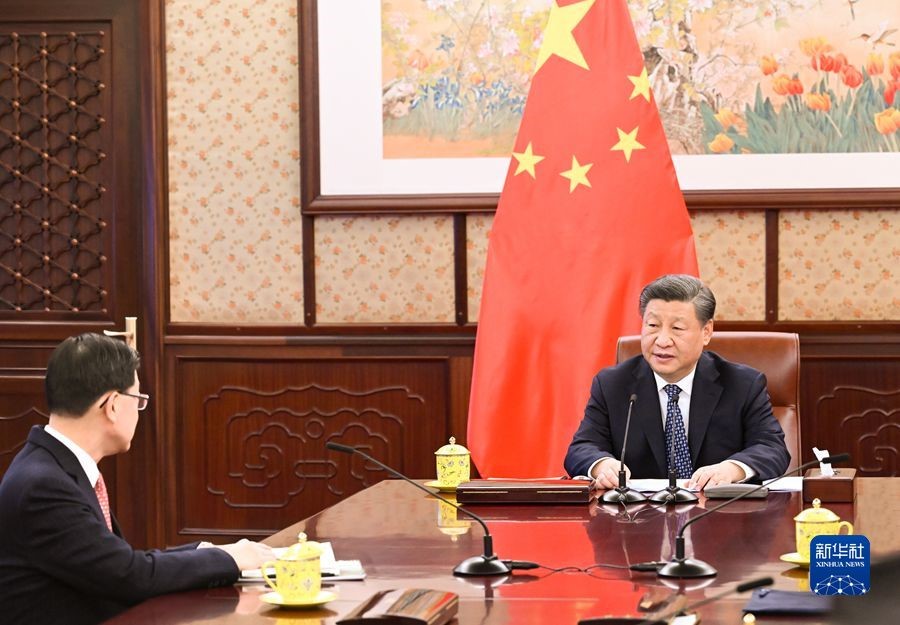

Photo: On December 23, President Xi Jinping met in Zhongnanhai with Lee Ka-chao, Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, who came to Beijing to report on his work. Xi has abandoned all promises regarding civil rights in Hong Kong. (Chinese govt. photo)